The Righteous Mind is a book about morals. At first glance, morality may belong to the realm of philosophers and theologians, but not actuaries. Indeed, it may be hard to find a discourse on the greater good in a statistics text book. Yet, there are three reasons I think actuaries will find this book appealing:

- Much of what actuaries are concerned with involves predicting human behavior. Perhaps understanding someone's moral framework can yield insights about their risk taking behavior or why they'd even consider buying insurance (or cheating the insurer).

- The book provides mathematical framework for morality. The author introduces the Morality Matrix, which should get the actuarial taste buds salivating. Haidt expands left/right orientations into a deeper palate of dimension. For actuaries who enjoy component based studies, this will be a welcome analysis.

- Actuaries are humans, too. This book offers a look in the mirror, an opportunity to "know thyself" a little bit better, and also sheds some light on your fellow human beings.

This book challenged some of the conventions I had about the role and value of

reason in my decision making and justifications It gave me an opportunity to

check my biases. Most importantly it gave me language/tools to understand the current political and social landscape in a way that the mainstream media misses.

Putting Reason in its Place

Haidt is a social psychologist, and as such much of the text is cracking open the skull to see what is happening in our minds. And out of the gates, one of the first items he addresses is Reason.

He argues that reasoning "has not evolved to help us find truth, but to help us engage in arguments, persuasion, and manipulation...". In other words, people won't arrive at a moral sentiment through logic, but instead use logic to justify whatever morality we posses.

As part of the evidence for flawed rationality, he provides an amusing ironic anecdote that in dozens of libraries the most common type of academic book that is never returned is a book on ethics.

Beyond that, studies about how much philosophers give to charity, call their moms, or do other noble actions, have shown that moral philosophers do no better than any other type of philosophers!

This leads to the cognitive bias predicament that we encounter so often. Haidt has a useful spin on the concept:

- If there is a conclusion we want to accept we ask ourselves can I believe this? In more actuarial terms, does it have a non zero chance of being true? When

- If there is a conclusion we don't want to accept, we ask ourselves, do I have to believe this? That is, is there a non zero chance of this being false.

The other challenging concept in this section was that we seem to care more about appearing virtuous than being virtuous.

To be honest, this section challenged me. Having a background in mathematics, reason has a lot of appeal. Form an equation, or derive a proof, to show that a + b = c. This can be validated and checked, and applied in the real world. Thankfully my actuarial training has given me an open mind to counterintuitive results, and it is hard to argue with the evidence.

Being WEIRD

Most actuaries are WEIRD, but I am not referring to our affections for science fiction and excitement around improbable events. Much of the profession comes from a background that is Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic. Turns out "WEIRD people are statistical outliers"!

"They are the least typical, least representative people you could study if you want to make generalizations about human nature." And yet most studies on the subject of human behavior have WEIRD populations as their base. By the way, perhaps unsurprisingly, Americans are even more abnormal than Europeans.

The cornerstone of the difference is interrelatedness. If you are WEIRD, the worldview is generally one where things are separate and independent instead of connected and relational.

Think of 5 sentences starting with "I am..."

Did you talk mostly about yourself? I am tall, I am an actuary, I am a fan of sports...

Or did you talk about your role in relationships? I am a father, I am a husband....

The American ethic generally revolves around individuals and freedom, whereas other cultures have more of a group orientation. To some degree this dynamic exists within the US as well. The importance of these worldviews is that they signal what sort of moral orientations will exist.

Haidt builds his matrix under three ethical principles about what people are:

- Autonomy - people are individuals with wants an needs and should be free to pursue these so long as they do not impose upon another's pursuits. This one should sound vey familiar.

- Community - people are first and foremost members of a family, tribe or nation and it is the group that matters most.

- Divinity - people are temporary vessels in which a scared soul is renting space.

It is the varying strengths of these worldviews that help explain the different moralities across the globe. By opening our minds to alternative understandings of who we are, we can begin to appreciate a boarder spectrum of morality.

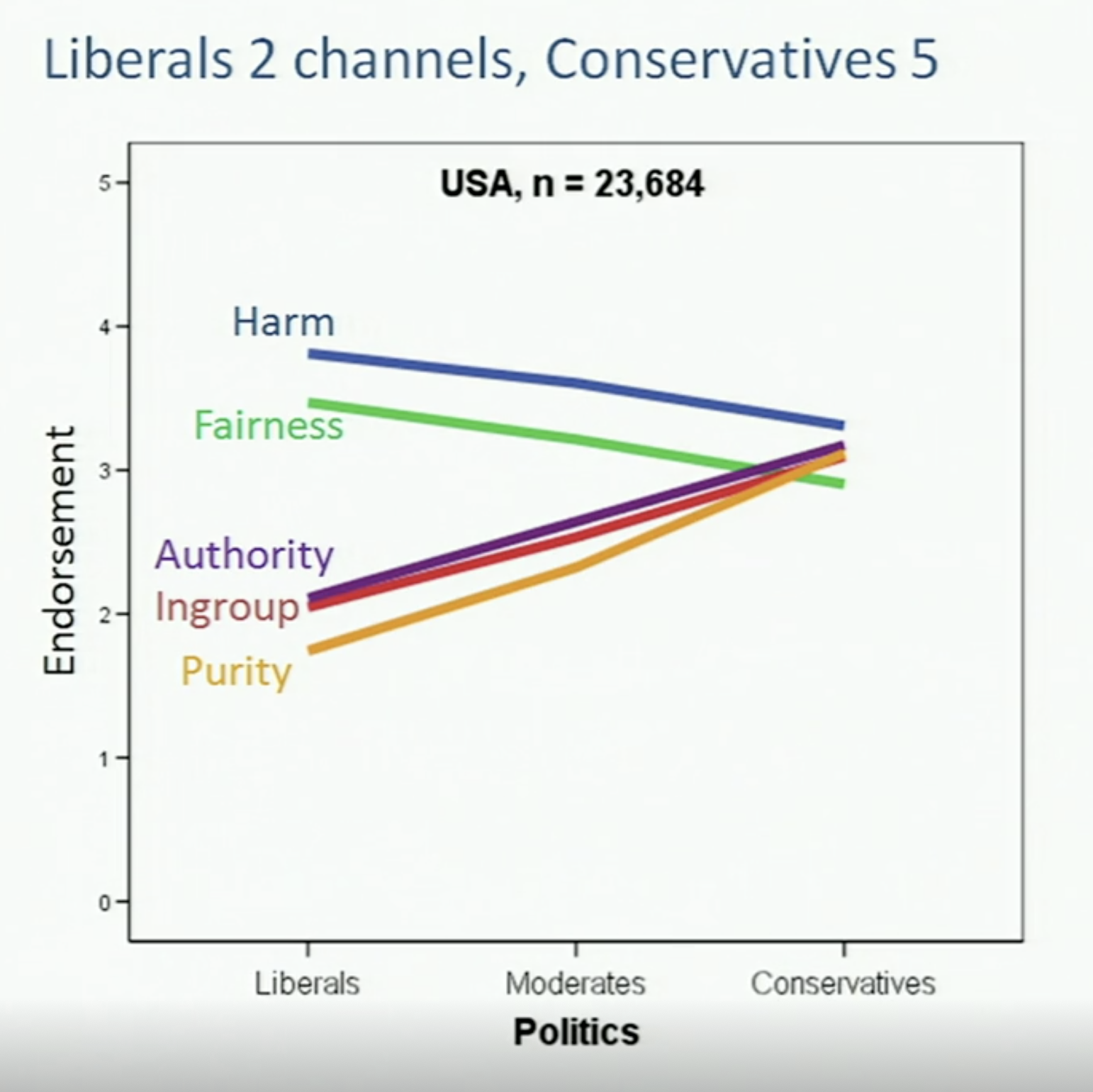

The Morality Matrix

For many of us, we recognize the sort of playground morality of don't hurt anyone, and share/take turns. This is the dominate orientation in the West, and particular among the political left. But Haidt introduces a a total of six dimensions.

- Care/harm

- Fairness/cheating

- Loyalty/betrayal

- Authority/subversion

- Sanctity/degradation

- Liberty/oppression.

I'll leave it to you to read through the book to fully understand what each of these elements involves, but I want to illustrate how this framework can help us understand how people act and why it is so difficult to have a constructive conversation in today's political climate.

As a heads up, Haidt's matrix will be particularly challenging the further left you are on the political spectrum. In one study when participants were asked to answer questions as if they were a conservative or a liberal, liberals were way worse at pretending to be conservatives. They seemed to view the conservative matrix as narrower than it actually is.

Case 1 - Vaccination and Masking

If you lean left, you likely support mandates vaccinations and masking primarily because not doing so would imply you would create unnecessary suffering to others. You are operating on the care/harm spectrum. And it will be very hard to consider points of view other than that. People are dying from COVID, hospitals are filling up, it should be blatantly obvious what the right thing to do is.

If you lean right, you probably accepted lock downs and masking initially, but as more people had asymptomatic responses to the disease and the virus started to slow down, you became eager to restore liberty and freedom. You weren't antivaccine per se, in fact you may have been vaccinated once people in your inner circle or someone you trust did the same. For you masking is less about the harm it prevents and is more about governmental overreach, and you worry about the slippery slope that would restrict even more freedoms.

What is important to see in this representation is that it doesn't make sense to pit Care/Harm against Liberty/Oppression. They are separate elements of the matrix and may have difficulty crossing communications.

- For the left - consider how to discuss masking and vaccination absent of the care/harm ethic. How could you normalize these behaviors such that it's what people would choose to do out of their own free will? Are there other moral grounds on which you could appeal?

- For the right - forget about the mandates for a moment, how would it feel if you knew you were directly responsible for someone's death? Spend some time focusing on the care/harm ethic exclusively and consider what sorts of things you would support that help reduce the harm of someone else?

Case 2 - Abortion

If you scour the political chatter around masking and vaccinations, you will likely find someone pointing out the hypocrisy of the right - it's my body, the government can't tell me what to do, unless I am a woman who wants an abortion.

The flaw in logic here, if we use the morality matrix, is that what appears to be hypocrisy is actually a symptom of the right having a broader moral spectrum.

In this case the concept of sanctity/degradation is the dominate value for the antiabortionists. In most cases the moral dimensions will complement each other, but it is entirely possible for them to be compartmentalized. In some cases liberty wins, in others, sanctity. The care/harm dimension may be at play here to some degree, but if you were to demonstrate that the act of abortion was done prior to consciousness for the fetus and without any harm to the mother, you would still have to have to overcome the intrinsic sense of 'wrongness' that would still exist.

And we can also reposition the left perspective a little bit - what seems like a liberty/oppression ethic may be more of a care/harm or fairness/cheating orientation. Abortion is symbolic of the harms of patriarchal systems against women. Rapists get away with violence, and women are penalized. Yes, the abortion discussion involves choice and freedom, but what makes it particularly charged for the left are these other elements on harm and fairness.

Exacerbating the problem of different moral dimensions is that this particular topic is very emotionally charged as well. It is a very carnal and visceral topic so it brings out our strongest passions. As such, coming to an acceptable consensus about legalized abortion may be impossible.

Instead, could we reshape the discussion to be about how we create environments in which the need for abortion is diminished? This might include education that covers both contraceptives AND abstinence. This might include finding ways to provide free healthcare to mothers who are willing to allow adoption, and to make the adoption process easier (including to non married, same sex partners). These types of discussions pivot to some different moral columns and can affirm both sides.

Getting Religious with Monkeys and Bees

Another part of the book that I found particularly interesting was Haidt's discourse on religion. He builds the case for religion to be viewed as something different than a relic from ancient human misapplication of "agency" hypothesis. (Attributing an unseen source to a observed event).

Haidt explains that evolution for humans seems to operate on an individual level (how do I advance my own genes) AND at a group level (because being in a groups helps us survive, and so we want the group to survive). In other words we are both apes competing for dominance and bees, working together for the sake of the hive.

Religion appeals to our hive side, and it gives power to certain behaviors that strengthen groups. "...the very ritual practices that the New Atheists dismiss as costly, inefficient, and irrational turn out to be a solution for one of the hardest problems humans face: cooperation without kinship."

This can be seen in the value of sacrifice. In anthropologic study, after 20 years comparing communes that demanded sacrifices from their members (giving up alcohol) secular groups had 6% survival rate, vs 39% for religious groups. A higher meaning gives power to behavior.

For more evidence, he points to studies on charitable giving. Religious people are more generous with money AND time, to their own churches for sure, but also to secular causes.

Has organized religion contributed to sexism, racism, and other forms of oppression's? Absolutely. It's power is both a blessing and a curse. In Haidt's word it "binds and blinds." Once something becomes 'sacred' a group becomes blind to the alternatives.

Returning to the vaccination scenario - what if the sacred was appealed to more than the science? Many religious groups adhere to a variety of rules about what to eat or wear and how to deal with infirmities on spiritual grounds.

And in other applications, how can the scientific community embrace the cooperative power of religious people to advance their causes?

Temet Nosce - Know Thyself

There a few more applicable takeaways from the text that I found interesting.

There may be a genetic/epigentic factor that influences our moral matrix. Studies of twins and siblings seem to suggest that our bodies may have different responses relating to new things and threats.

- If our internal chemistry responds more strongly to new things we may be more comfortable changing systems - more progressive

- If our internal chemistry responds more strongly to threats we may prefer stability and resist chance - more conservative

This is not a lock and our future is malleable, but it is important to recognize how you might be prewired.

Knowing you bias - there are two tools presented in the text that I encourage people to check out:

- The Implicit Assumption Test offers ways for you to see if you have unconscious associations with race or body time or gender. As an example, let's say I think I don't have a bias against dentists. The test will show me an image of dentist and then a positive word ('happy') or negative word ('sad'), and depending on the lag it takes be to identify the word category after the image, I will have some indication of my prejudice. For example, I I found out I am somewhat more biased toward associating males with science and math.

- Your Morals - gives you a chance to see what dimensions matter to you more.

In sum

Haidt's book is a challenging exploration into the sources of morality and its role in our societies. He gives vocabulary to the complexities of our moral fabric. Hopefully it can help us understand ourselves and others a little better and create a platform for a more civil discourse.

No comments:

Post a Comment